Excerpt from ‘War Survivor

(1968)’Biafra-Nigeria

Outrunning my approaching death.

Flying high over stalls, strewed paths

My palm-oil bottle clutched in my right handI am a six-year-old, fleeing exploding bombs

resisting death

smelling death

hearing deathI am a small boy on an errand;

obeying my grandma’s order to

buy palm oil in the market;

Nigeria’s fire-spitting birds on an errand;

obeying a general’s order

selling bloody deals in the market

– memory of hidden away traumaNimi Wariboko

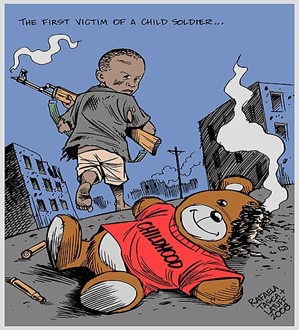

Nimi Wariboko, today a Professor of Social Ethics at Boston University, used poetry to narrate his childhood memories of the Nigerian-Biafran civil war of 1967-70. Nimi was a six-year-old boy when the war came to his town, Abonnema in 1968, a minority Ijo community in the River State. In his collection Songs of Childhood, memory takes lyrical form, bearing witness to the collision of childhood and war in a moving insight into lived experience of the thirty-month conflict that had enduring legacies. Nimi writes in the preface to his collection, “What I have done is to pan the camera to the fate of the minority-Ijo group of the Abonnema people. Usually, stories of war are tales of grandeur, involving big people and big places…. This is a historical document.”

I interviewed Nimi as part of our oral history research on children’s experiences of the war. In our discussion, we explored several of Nimi’s reflective poems, including ‘War Survivor’, in which he describes the moment bombs fell on his local marketplace, where he had been sent to buy palm oil for his grandmother.

I lived about half a mile or less from the main market… [my grandma] had sent me to go buy palm oil. She gave me the bottle to go. I was at the market, bought the palm oil and was about to leave. The bombs fell and most people died. I happened to be one of the survivors. I ran with the bottle in my hand up to my house… When I got back, they said, “Why didn’t you drop it?” They couldn’t believe it. I don’t know why! I just carried it. It was not damaged at all.

Of all the poems we explored and all the recollections of war Nimi shared, this moment lingered with me the longest. The image of young Nimi sprinting through a marketplace turned to rubble with oil for his grandma preserved safely in his hand embodies the paradox of childhood in war: the routine nature of a child’s chore carried out amidst the chaos, literally clutching at the thread of normalcy as he ran from the destruction.

Nimi draws a striking parallel in this poem between his blind focus on his errand and that of the Nigerian pilots who dropped the bombs, similarly carrying out their ‘errand; obeying a general’s order’. This mirroring hints at how a young Nimi made sense of his experience in the marketplace, framing the behaviours and hierarchy of the attacking armed forces against his own familiar family roles. In other poems in his collection, Nimi similarly applies an expressive comparative lens to reconcile the disorienting violence he observed with his child self’s frame of reference. In ‘Mercenary War Pilot and a Boy’, Nimi retells the moment a ‘white man, with black hair and headphones’ flew his plane over the village. In our interview, he explained:

Our eyes met and he winked at me, because he was actually flying low and slow. He winked at me, and then dropped a bomb. He went two or three houses along and dropped the bomb. And I know the girl that was killed—and her mother who survived.

This poem ends with a poignant memory of his friends and peers playfully mimicking the destruction of this bomber plane:

Fear lurked in the hearth

Play was still plentiful.

Children made clay models of fighter jets

They bombed, they dived, they tossed up dust

They whirred, they whirled, they squawked

They played, they laughed, played, laughed…

Our project examines the generational dimensions of conflict—how age shapes experiences, behaviours, roles, and memories. Through Nimi’s poems and his recollections, we glimpse the layers of violence, joy, resilience and suffering that shape his memory. Like other war-affected children who have turned to authorship to memorialise their experiences (Beah, 2008; Jal, 2009: McDonnell & Akallo, 2007), Nimi felt strongly that the act of writing helped him to make sense of the story of his life. According to Gillian Whitlock, writing one’s life can ‘humanise categories of people whose experiences are frequently unseen and unheard’. This was, Nimi explained, particularly important to do from a minority child’s perspective, for whom opportunities to participate in other healing and reconciliation initiatives were lacking.

After what I saw [in the war], I just couldn’t talk. I would sit at the window and look at the sky for a long time. When I tried to talk again, I had a stammer. So I am trying to capture these experiences as much as I can… now [since publication], people are calling me up. They’re saying, write about this part, or do you remember this? These are all people who had things to tell but have not had the ways to express themselves.

Extant literature largely supports the value of creative arts for healing in war-affected children (Frasco et al., 2025). Studies have shown creative outlets can significantly reduce symptoms of negative mood and foster hopeful attitudes towards the future (Morison et al., 2021; Harris, 2007; Green & Denov, 2019). From a historian’s perspective, memoirs and other self-reflective literature written by war-affected children are highly productive resources for what they reveal about the ‘quotidian realities of conflict’ (Hynd, 2021). Read, as Nimi claims, as a historical document, the bottle of palm oil carried carefully from the bombsite to Nimi’s house becomes more than just a detail—it becomes a reminder that in every war, children are not only caught in the crossfire: they are also holding stories, holding meaning, and sometimes, against all odds, holding on.

Citations

Ishamel Beah (2008), A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Child Soldier (London: Harper Perennial)

Eric Frasco et al. (2025), ‘The impact of creative arts-based interventions for mental health in conflict-affected contexts: A systematic narrative review’, SSM Mental Health 7, 100419

Amber Green & Myriam Denov (2019), ‘Mask-Making and Drawing as Method: Arts-Based Approaches to Data Collection with War-Affected Children’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18: 1-13

David A. Harris (2007) ‘Pathways to embodied empathy and reconciliation after atrocity: former boy soldiers in a dance/movement therapy group in Sierra Leone’, Intervention, 5, 3: 203-231

Stacey Hynd (2021), ‘Trauma, Violence, and Memory in African Child Soldier Memoirs’, Cult Med Psychiatry, 45: 74-96

Emmanuel Jal & Megan Lloyd Davies (2009), Warchild: A Boyd Soldier’s Story (London: Abacus)

Faith McDonnell and Grace Akallo (2007), Girl Soldier: A Story of Hope for Northern Uganda’s Children (Grand Rapid: Chosen Books)

Linda Morison et al. (2021), ‘Effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions for treating children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events: a systematic review of the quantitative evidence and meta-analysis’, Arts & Health, 14, 3: 237-262

Gillian Whitlock (2010), Soft Weapons: Autobiography in Transit (University of Chicago Press)