As part of the broader research on histories of child soldiers in Africa, we are engaging with the existing monitoring of children in armed conflict internationally, including the reports of the Secretary-General of the United Nations and the United Nations Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict. We anticipated that this would be a good way to link our historical project with contemporary prevalence data. We have found that the prevalence data is also useful for revealing the processes of humanitarian knowledge construction and norm evolution. This blog series contains methodological reflections and critiques founded in our unfolding attempt to construct our own historical dataset of children in armed conflict.

The main data page, where we discuss the mapping methodologies and sources, is here.

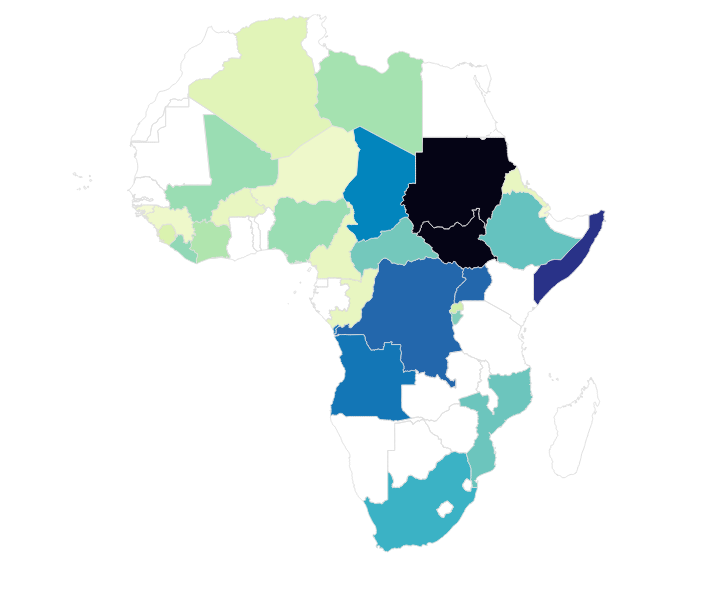

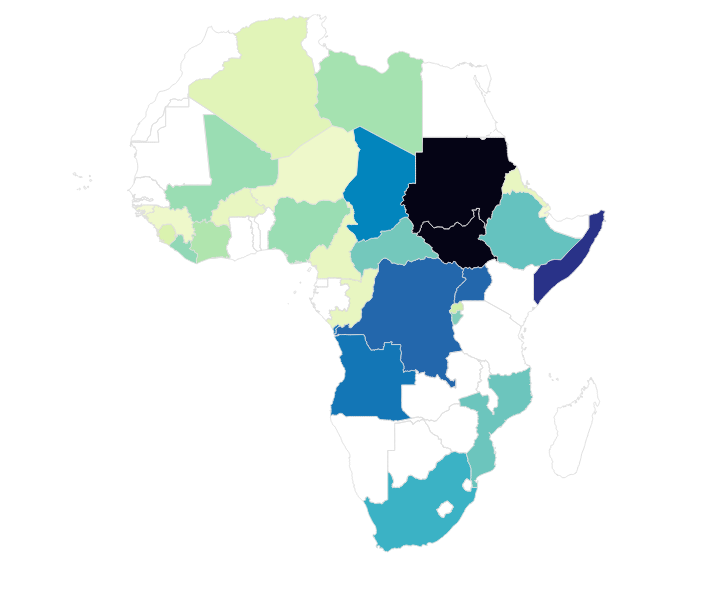

This map shows the number of years with reported child soldier use, 1970-2022.

The first phase of our mapping project is based on numbers and data reported in human rights and humanitarian monitoring and advocacy documents (see the Methodology). With this first blog in the series on data and numbers, we discuss the mapping source material and the evolution of monitoring violations against children in armed conflict.

The office of the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict was created in 1996, reflecting the growing focus on children and youth as categories of particular concern in humanitarian response and governance structures, as seen in the 1996 Machel Report on ‘The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children’. The first Secretary General report on Children and Armed Conflict (2000) included the widely-cited ‘zombie number’ (Hynd 2021, 273) of 300,000 ‘children under the age of 18 who have been coerced or induced to take up arms as child soldiers’ (SecGen 2000, para. 2). The UN Secretary General reports built on two decades of transnational advocacy that had tracked developments in child soldiering but faced challenges in securing quantitative and comparative data.

Evolution of UN Monitoring

1998: First Open Debate on Child and Armed Conflict held at the UN Security Council

1999: UN Security Council Resolution 1261 (identifies long-term consequences of children affected by war for ‘durable peace, security and development’). Also identified ‘six grave violations’: recruitment & use, killing & maiming, sexual violence, abduction, forced displacement and attacks on objects protected under international law (schools/hospitals).

2000: Resolution 1314 urges all parties to armed conflict to respect fully international law applicable to the rights and protection of children in armed conflict; underlines the importance of giving consideration to the special needs and particular vulnerabilities of girls affected by armed conflict, including those heading households, orphaned, sexually exploited and used as combatants.

2001: Resolution 1379 requested the Secretary General attach to his report a list of parties to armed conflict that recruit or use children.

2004: Resolution 1539. Called for comprehensive reporting mechanism. In response to that, the secretary-general’s fifth report included an action plan for the establishment of a mechanism to monitor the six grave violations of children’s rights in situations of armed conflict: (1) killing or maiming of children; (2) recruitment or use of child-soldiers; (3) attacks against schools or hospitals; (4) rape or other grave sexual violence against children; (5) abduction of children; and (6) denial of humanitarian access for children, the last of these being the only violation that is not a trigger for listing.

2005: Resolution 1612 called for immediate implementation of the MRM (Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism) established for situations that lead to state or nonstate parties being included in the list of shame.

2008: Shift in reporting period, [September 2007-December 2008; January-December 2009]

2009: Resolution 1882 added two new criteria for listing/delisting parties: parties who kill & maim children and who commit rape/sexual violence against children in armed conflict situations

2011: Resolution 1998 – added attacks against schools and hospitals.

2014: Resolution 2143 and launch of ‘Children, Not Soldiers’. Representatives from Afghanistan, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen attended the launch event and pledged their full support in reaching the objectives of the campaign.

2015: Resolution 2225 expanded on the triggers for listing by including the abduction of children in situations of armed conflict (post Boko Haram abductions).

Since the first report in 2000, the Secretary General and Special Representative reports have monitored the use of children in armed conflict, including tracking negotiated agreements and progress on commitments to demobilize or not use children. If you read the most recent Secretary General ‘Annual report on children and Armed Conflict’, you would be forgiven for imagining a standardized and systematic reporting procedure. The reality, of course, is that the reports are the end result of a long process of observations, allegations, diplomacy, reports, meetings, consolidations, and debates over what constitutes evidence. As such, these reports offer a window into the construction of humanitarian knowledge and legal-political norms. The numbers which appear with increasing frequency in the report – from the institution of the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism in 2005 – are a more accurate reflection of growth in humanitarian infrastructure around knowledge and monitoring than a depiction of the actual numbers of children and youth involved in armed conflicts across the world. This reflects the challenges of documenting and verifying numbers of children and youth involved in conflict.

The problem of quantifying child soldiering/violations against children in humanitarian data was immediately revealed when we began building our dataset from the Secretary General reports. These reports contain few concrete datapoints, overlap categories and duplications, and tend to describe rather than quantify violations.

“Children were recruited between May and July 2006, in Khartoum, Jonglei and Bahr al-Ghazal by the Sudan Armed Forces and SPLA. For example, on 16 May 2006, the Sudan Armed Forces, SPLA and the new Joint Integrated Units were all reported to be involved in recruiting children in Nasser, Upper Nile State. In the same month, child soldiers were seen in a newly incorporated Sudan Armed Forces unit near Nasser, and there were reports of approximately 50 uniformed and armed SPLA soldiers aged between 14 and 16 years in the same area.” (Para 73: Secretary General Report 2007).

This quote demonstrates the complexity of reporting sources, tracking multiple armed groups, balancing sightings and reports with confirmed incidents of recruitment across large spans of time and space, and attempting to assess age categories based on scant evidence. Documenting and verifying these reports and sightings sufficiently for inclusion in Secretary General reporting is a difficult task. The Secretary General reports attempt an annual monitoring – leaving them at the whim of shifting access, politicization of allegations and reporting mechanisms, and the complexity of conflict dynamics. These reports, and how they change across years, reveal the challenges of monitoring and enumerating the involvement of children in conflict.

In contrast, the pre-2003 data – drawn from advocacy documents, archives, and secondary conflict datasets (see methodology) – was largely drawn from media reporting and anecdotal evidence and gives only broad ranges for child soldier numbers sometimes as wide as 5,000 – 20,000. This captures the breadth of allegations but little in the way of detail. Numbers are also estimated cumulatively across the duration of a conflict, eclipsing nuances of recruitment drivers or sub-national variation. Reporting was frequently retrospective, generated by advocacy groups and researchers at the conclusion of a conflict on the basis of demobilization observations, or even years after the end of fighting.

Work with these available numbers to undertake any quantitative visual analysis of the patterns and trends in children’s military recruitment and use has proven challenging. The inconsistency of recruitment and use estimates makes using these numbers as ‘fact’ unreliable – as discussed in our blog on intensity of recruitment and use. Instead we have found that the data is most effective at illustrating the breadth and longevity of use, as we have attempted in the map below. This visual representation highlights longstanding recruitment sites such as in Sudan and South Sudan, with allegations corresponding to 42 out of the 52 years captured in the data.

This map shows the number of years in which there is reported recruitment and use of children in conflict, 1970-2022. This does not account for the number of children used.

Mapping the numbers produced by these humanitarian and advocacy sources illustrates glaring gaps in the data – particularly silences in southern and northern Africa to start. There were conflicts in many of these countries, as well as documented examples of cross-border recruitment and training, within the period of analysis yet they are absent in the data. This highlights limitations of the initial dataset, as well as problems with mapping along contemporary national demarcations which are contested and have shifted during the period of analysis.

We aim to engage with questions of cross-border and (trans)national dynamics, and with shifting patterns and trends over time in other blogs and publications. In subsequent blogs in this series we will dig in on specific areas of the data – around the lack of quantifiable data, demobilization, observations and age categories, categories of violation – which help us tell different kinds of stories.

Phoebe Shambaugh & Chessie Baldwin

References

Stacey Hynd, ‘Constructing the Child Soldier Crisis: The Development of Transnational Advocacy and Humanitarian Campaigns against the Recruitment and Use of Children in Conflict, c.1970-2000’, Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 12.3 (Fall 2021), 265-85. doi.org/10.1353/hum.2021.0017

Data Sources

‘Children of War: a newsletter on Child Soldiers from Radda Barnen’ (1996 – 1998) <https://web.archive.org/web/19970102033609/http://www.rb.se/chilwar/fem_96/cw53.htm>

Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, ‘Child Soldiers Global Report 2004’, <Child Soldiers: Global Report 2004 – World | ReliefWeb>

Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (Switzerland), The use of children as soldiers in Africa: a country analysis of child recruitment and participation in armed conflict (UNESCO digital library, 1999)

Secretary-General Annual Report on Children and Armed Conflict (2002 – 2023)

Swarthmore College Peace Archives, Dorothea E. Woods Collection, SCPC DG 213 series.

Rachel Brett and Margaret McCallin, Children: The Invisible Soldiers (Radda Barnen, 1996)

Vera Achvarina and Simon F. Reich, ‘No Place to Hide: Refugees, Displaced Persons, and the Recruitment of Child Soldiers’, International Security, 31, 1 (2006); 127-164