Current humanitarian norms, as outlined in the 2007 Paris Principles, define child soldiers as “any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes”.[1] This project reads this definition backwards in time, applying it to conflicts and individuals across twentieth century Africa, to trace historical patterns of children’s military recruitment and use. This methodology reveals the tensions around and challenges to the label of ‘child soldier’.

Firstly, childhood is not a universal category: it is historically and culturally contingent, with marked differences between global norms and local African understandings of childhood.[2] It also overlaps with the category of ‘youth’. Youth is as much a social and political as chronological category, but commonly applies to those between the ages of 14 to 40: as the majority of ‘child soldiers’ are 15-17 years, many claim the label of ‘youth’, thereby highlighting their political agency. Gender can be as significant as age in shaping children’s military experiences.

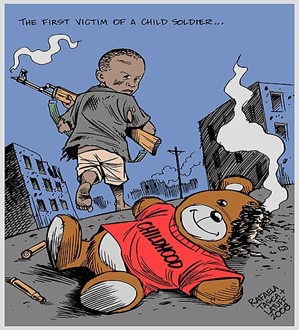

Military service itself is regarded in many cultures as a marker of adulthood, and therefore underage soldiers who are chronologically under 18 often consider themselves as ‘adults’ rather than children due to their military status and experience. In other cultures however, such as in South Sudan, communities may still regard chronologically and biologically-adult former underage recruits as ‘boys’ because they have not undergone then required processes and rituals of initiation to be regarded as adult men, where these initiations were interrupted by war.[3] Before the mid-1990s the ‘child soldier’ was almost universally coded as male, but it is now recognised that around a four in ten of underage troops are ‘girl soldiers’ .[4]

Secondly, the category of ‘soldier’ itself does not fully address children’s participation in armed conflict and violence. Many children do not bear arms, and are instead involved in support roles, or move between front line and auxiliary roles. However, communities and individuals still commonly ascribe the label of child soldiers only to those with guns. Categories of war and armed forces or groups also require interrogation. Teenagers fighting the apartheid regime in South Africa, particularly in the African National Congress’ armed wing, are not regarded ‘child soldiers’ but broadly fit current definitions. Many young African anti-colonial ‘insurgents’ or ‘freedom fighters’ from the 1950-80s would today be classified as ‘child soldiers’.

Thirdly, the ‘child soldier’ as a humanitarian category has acquired particular connotations that can drive individuals to claim or reject it. Some avoid it due to potential stigmatization where this global label has come locally to hold connotations of violent perpetration and human rights abuses, as with the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda. Instead, they lay claim to alternative identities, as ‘freedom fighters’ or ‘veterans’, to gain social status or access support. Concerns about stigmatizing current and former underaged soldiers led many advocacy and child/human rights groups to drop the label ‘child soldiers’ in favour of ‘child [formerly] associated with armed forces and armed groups’, or CAAFAG. The lack of transparency of this acronym however means that the term ‘child soldier’ remains common outside of these circles.

Conversely, some former under-age fighters now deliberately adopt the category and language of contemporary human rights-based ‘child soldier’ discourses. This can be as part of a victimcy narrative to access available Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (DDRR) support and resources. Those who served as minors in conflicts prior to the emergence of the ‘child soldier crisis’ in the late 1980-1990s have also appropriated the label. Former underage Biafran combatants from the Nigerian-Biafran civil war (1967-70) frame their narratives as ‘child soldier memoirs’ to highlight their war contributions and locate their experiences within global narratives of victimhood. In doing so they differentiate between their version of ‘child soldiering’ for community defence and the present-day exploitation and abuse of children by Boko Haram in northern Nigeria.

[1] UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), The Paris Principles. Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated With Armed Forces or Armed Groups, February 2007. https://www.refworld.org/reference/research/unicef/2007/en/42827.

[2] See Allison James, Chris Jenks and Alan Prout, Theorizing Childhood (Cambridge: Polity Press, [1998]2015).

[3] See Deng Adut with Ben McKelvey, Songs of a War Boy (2017)

[4] See https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/2015/02/4-10-child-soldiers-girls/